A Few Words on Wake Now In The Fire by Jarrett Dapier

Persepolis at the Center of the Fire: What Wake Now in the Fire Taught Me About Books That Refuse to Behave

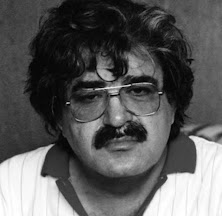

Reza Shirmarz

I used to imagine censorship as something loud.

A shouting match at a school board meeting. A dramatic scene. A moral panic with a microphone.

But Wake Now in the Fire reminded me that in real life censorship is often quiet, so quiet it can hide inside “normal” work. It shows up as an email, a bullet list, a deadline. And the book at the center of this particular storm, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, is not just a title. It becomes a body that institutions try to move, contain, rename, and “process.”

There’s a moment in the novel where the principal’s message is relayed as a set of instructions. You can almost hear the administrative voice trying to sound neutral: go into each school, confirm the book isn’t in the library, confirm it hasn’t been checked out, confirm it isn’t being used, and then collect it, by Friday. No explanation is provided.

That’s the first gut-punch: the attempt to remove Persepolis arrives not as an argument, but as a procedure.

Why Persepolis matters here... specifically?

It isn’t random that Persepolis becomes the battleground.

Satrapi’s memoir is a story of growing up under political upheaval, war, and authoritarian control, where the state reaches into everyday life and tries to govern what you can say, what you can read, what you can wear, and how you are allowed to be visible. And Wake Now in the Fire turns that into a painful irony: a book that narrates repression becomes the occasion for a school system to rehearse its own version of repression, then deny that it’s doing it.

The novel even embeds a brief “about the author” passage (the kind of paratext most people skim). But here it matters because it underlines something basic: Satrapi is an Iranian-born writer and artist living in Paris; she made Persepolis, and its film adaptation was internationally recognized.

In other words: this isn’t fringe material. It’s a major work of contemporary memoir and comics.

And yet the system treats it like contraband.

The actual mechanism: a ban that doesn’t want to say “ban”

One of the smartest things Wake Now in the Fire does is show how institutions protect themselves rhetorically. They don’t just control access; they try to control the word for what they’re doing.

At a press conference, when a reporter asks about the removal, CPS leadership responds with disbelief and dismissal, calling it “made up,” and insisting, “CPS teaches students; we’re not in the business of censorship.”

That sentence is doing more than denying a claim. It’s trying to take away the vocabulary students need in order to resist.

If you can’t name it “censorship,” then you’re stuck arguing over softer terms, miscommunication, confusion, appropriateness, clarification. The novel makes you feel how power works through euphemism: deny the name, keep the effect.

Persepolis as a test of what a library is supposed to be

If the memo is the story’s cold machinery, the library is its warm counterforce.

One line from the librarian hit me harder than a speech ever could: “This is a library. Our books are for reading.”

It’s such a simple claim, and that’s why it’s radical. It refuses the idea that access is a privilege granted by the institution’s mood. It frames the library as a promise.

And then the librarian does something equally important: she forwards the principal’s email up the chain and asks the Department of Libraries if they know what’s happening, insisting that this order, if it touches the library, must be taken seriously and examined.

This is what resistance often looks like inside institutions: not heroic rebellion, but the decision to treat a directive as challengeable.

Later, a clarification comes in: the directive to remove Persepolis does not apply to school libraries, and any attempt to remove it must follow the Collection Development review procedure.

That detail matters because it reveals what censorship fears: process. A real review creates a paper trail. It forces reasons into the open. It makes power accountable.

And once the students and staff learn that, they pivot. One teacher even jokes about the librarian “turning all my copies into library copies with her magic scanner,” precisely because library copies are protected by policy.

In other words: the same world that tried to erase a book through procedure gets answered back through procedure.

Persepolis as a public object: reading becomes protest

When the system tries to remove Persepolis, the students do the thing censorship never anticipates: they make the book more visible.

They plan a protest,

time, place, bodies, sound. “Stand in solidarity” at Western and Addison at 2:30 on Friday; if you have noisemakers, bring them; if nobody gives permission, walk out anyway.

This is the part that feels deeply rhetorical to me. Not “rhetoric” as polished speech, but rhetoric as presence, coordination, and public attention. A book becomes a reason people gather. Reading becomes an act you can see.

Even the social-media fragments the novel includes capture how quickly the story shifts from local rumor to public event. One post says what many people quietly assume: “Bet it’s bc it’s a comic.”

That line is important. It points to a prejudice that still survives: the suspicion that the comics medium is “less serious,” or “too visual,” or therefore more dangerous. But Persepolis is exactly the book that defeats that prejudice, because its visual simplicity is part of its moral force.

Persepolis as journalism: students widen the audience

One of the most powerful acts in Wake Now in the Fire is a student journalist writing to the publisher. He identifies himself as co-editor of the school paper and says they’ve learned the book has been banned, copies removed, and they don’t know why. Then he asks the question that turns a school issue into a public issue: what is Satrapi’s response?

This moment matters because it shows literacy as something bigger than interpretation. Literacy here becomes circulation and accountability:

Who can make a statement?

Who gets quoted?

Who gets heard outside the building?

Who gets to define what happened?

When an institution tries to control the story internally, students move the story outward.

The most “teacher” moment in the whole book

There’s a classroom scene I keep thinking about because it refuses the easy myth that censorship is something “those other people” do. A teacher pushes students to research: what books have been banned in America, under what settings, and why, and how this squares with the First Amendment.

That’s pedagogy as empowerment. It says: don’t just feel outrage, learn the patterns, the history, the mechanics. Learn how censorship travels.

And that’s exactly what the students end up doing in real time.

What Wake Now in the Fire ultimately shows about Persepolis

In this novel, Persepolis becomes more than content. It becomes:

A mirror (a memoir about repression mirrored by an institutional attempt to restrict reading).

A test (of what a school is: a place of inquiry or a place of managed visibility).

An engine (the object that produces organizing, journalism, and public confrontation).

A lesson in medium (how “it’s a comic” becomes part of the stigma, while the comic form becomes the very tool of testimony).

And personally? It reminded me why certain books keep getting targeted. It’s not always about a single panel or a single scene. It’s often about what the book trains you to do: to compare official narratives with lived ones, to notice contradictions, to ask who benefits from silence.

That’s what Persepolis teaches. And that’s why it becomes the beating heart of Dapier story: because the moment you remove that book, you’re not only policing a curriculum, you’re trying to police a habit of mind.

And students, in this novel, refuse to let that happen.

Comments

Post a Comment