My Uncle Napoleon by Iraj Pezeshkzad

A short Analysis by Reza Shirmarz

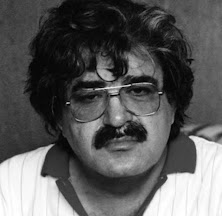

Iraj Pezeshkzad (1927–2022) was a celebrated Iranian writer, translator, and diplomat, best known for his brilliant social satire. Born in Tehran into a prominent family, his mother a Qajar aristocrat, he studied law in France before entering Iran’s judiciary and then its foreign service and served as a judge for five years and later as a diplomat until the 1979 revolution. A versatile literary figure, Pezeshkzad began writing in the early 1950s. He translated works by Voltaire and Molière into Persian, contributed short stories to magazines, and edited satire for the Towfigh weekly. His bibliography spans novels, plays, political essays, and historical works, including the widely enjoyed Haji Mam‑ja‘far in Paris, Asemun Rismun, and Hafez in Love. His masterpiece, the 1973 novel My Uncle Napoleon, cemented his literary reputation. This caustic, affectionate comedy set in 1940s Tehran skewers paranoia and social absurdities and quickly became a cultural phenomenon, later adapted into a beloved television series. Translated into multiple languages, including an acclaimed English edition with an introduction by Azar Nafisi, the novel remains a touchstone of Persian-language literature. After the revolution, Pezeshkzad went into exile in France and aligned himself with the National Resistance Movement alongside Shapour Bakhtiar. He continued his literary and journalistic work abroad and published political writings and memoirs, including his autobiography The Pleasure‑Grounds of Life. He died in Los Angeles at age 94, leaving behind a legacy marked by humor, historical insight, and enduring cultural resonance

Iraj Pezeshkzad (1927–2022) was a celebrated Iranian writer, translator, and diplomat, best known for his brilliant social satire. Born in Tehran into a prominent family, his mother a Qajar aristocrat, he studied law in France before entering Iran’s judiciary and then its foreign service and served as a judge for five years and later as a diplomat until the 1979 revolution. A versatile literary figure, Pezeshkzad began writing in the early 1950s. He translated works by Voltaire and Molière into Persian, contributed short stories to magazines, and edited satire for the Towfigh weekly. His bibliography spans novels, plays, political essays, and historical works, including the widely enjoyed Haji Mam‑ja‘far in Paris, Asemun Rismun, and Hafez in Love. His masterpiece, the 1973 novel My Uncle Napoleon, cemented his literary reputation. This caustic, affectionate comedy set in 1940s Tehran skewers paranoia and social absurdities and quickly became a cultural phenomenon, later adapted into a beloved television series. Translated into multiple languages, including an acclaimed English edition with an introduction by Azar Nafisi, the novel remains a touchstone of Persian-language literature. After the revolution, Pezeshkzad went into exile in France and aligned himself with the National Resistance Movement alongside Shapour Bakhtiar. He continued his literary and journalistic work abroad and published political writings and memoirs, including his autobiography The Pleasure‑Grounds of Life. He died in Los Angeles at age 94, leaving behind a legacy marked by humor, historical insight, and enduring cultural resonance

Iraj Pezeshkzad’s My Uncle Napoleon is widely regarded as one of Persian literature's most enduring satirical masterpieces. Written in the 20th century and set against the backdrop of World War II, the novel weaves humor, love, and cultural critique into a rich narrative tapestry. Through the lens of familial relationships, personal desires, and societal norms, the novel examines human behavior with a mix of levity and poignant insight. At its core, My Uncle Napoleon critiques societal structures and explores themes of love, paranoia, and patriarchal power, while capturing the complexities of individual emotions and family politics. The narrator’s love for his cousin Layli serves as the emotional backbone of the story. This unspoken and unfulfilled passion embodies youthful idealism and romantic longing, which clash against the rigid social frameworks of their family. The narrator’s first encounter with Layli’s gaze, “I couldn’t tear my gaze away from hers”, marks the beginning of his internal struggle. His feelings remain private, and the societal and familial constraints placed upon him emphasize the difficulty of pursuing love in such an environment. Familial obligations, patriarchal traditions, and generational divides complicate this love and renders it both an idealized dream and a source of immense pain.

The obstacles to the narrator’s love reflect larger societal restrictions. Uncle Napoleon, as the patriarch of the family, epitomizes the oppressive nature of tradition. He enforces rigid rules, often wielding his power arbitrarily. The narrator’s father, who clashes with Uncle Napoleon, represents a potential ally but is himself a victim of the familial power structure. This power dynamic mirrors broader cultural tensions between individual desires and societal expectations. The narrator’s love for Layli, while personal, becomes a metaphor for the universal struggle to balance personal freedom with the constraints of tradition.

Pezeshkzad’s use of references to Persian and Western romantic traditions further enriches this theme. The narrator reflects on archetypes like Layli and Majnun, Iran’s legendary lovers, and compares his feelings to Western classics like Romeo and Juliet. He wonders whether he, like these figures, is doomed to suffer the “death and disaster” often associated with love. The interweaving of these cultural motifs not only highlights the universality of the narrator’s emotions but also demonstrates the ways in which different traditions grapple with love as both a transcendent ideal and a source of tragedy.

At the heart of the novel’s satire is Uncle Napoleon’s obsession with British conspiracies. His conviction that the British are behind every misfortune serves as both a personal eccentricity and a broader commentary on Iranian society’s historical paranoia. Uncle Napoleon declares, “The British are behind every misfortune!”, a refrain that depicts his exaggerated distrust. This paranoia, while absurd in its scale, is rooted in historical realities. Iran’s geopolitical position during the 19th and 20th centuries made it vulnerable to interference from foreign powers, particularly Britain and Russia. The novel, set during World War II, captures this historical tension while poking fun at the irrationalities it engendered.

Uncle Napoleon’s paranoia extends to the point of absurdity, as illustrated by his letter to Hitler, in which he positions himself as a strategic ally in the fight against Britain. This act, simultaneously humorous and pathetic, showcases the delusional nature of his worldview. Through such scenes, Pezeshkzad critiques the destructiveness of conspiracy theories, which not only isolate individuals like Uncle Napoleon but also fracture relationships and impede progress. The character’s exaggerated distrust reflects a microcosm of Iranian society’s historical and cultural anxieties, which makes his paranoia both a source of humor and a tool for social critique.

Uncle Napoleon’s character also embodies the patriarchal systems that dominate the family and, by extension, society. As the self-appointed head of the family, he controls nearly every aspect of their lives. His authoritarian tendencies are exemplified in his decision to cut off the water supply to the narrator’s family, an act that manifests his willingness to wield power punitively. Uncle Napoleon’s obsession with Napoleon Bonaparte, whose military exploits he admires, further emphasizes his need to see himself as a heroic figure. Yet, his fabricated tales of personal bravery, often borrowed from Napoleonic history, expose the fragility of his ego.

The dynamics of power within the family also highlight the generational divide between the older, more traditional members and the younger, more modern characters. Uncle Napoleon’s resistance to change is contrasted with the quiet defiance of the narrator and Layli. This generational tension illustrates the broader clash between tradition and modernity, a recurring motif in the novel. Women, too, are caught within these patriarchal structures. Characters like Layli and Qamar have limited agency, as their lives are dictated by male authority. Qamar’s marriage negotiations, for example, reveal the transactional nature of such arrangements. While Layli’s resistance to these norms is subtler, her quiet rebellion highlights a desire for greater autonomy.

The extended family, with its alliances, rivalries, and constant negotiations, serves as a microcosm for Iranian society. Relationships within the family are shaped by tradition, personal ambition, and societal norms. The narrator observes these dynamics with a mix of curiosity and frustration while recognizing both their absurdities and their emotional weight. Humor becomes a critical coping mechanism for the family, which assists to alleviate tension while also exposing their flaws. Characters like Dustali Khan and Asadollah Mirza, whose antics provide comic relief, balance the more oppressive aspects of Uncle Napoleon’s authoritarianism. The interplay of humor and drama captures the richness of family life while critiquing its constraints.

The tension between tradition and modernity is perhaps most vividly depicted in the novel’s setting. The shared family compound, where generations live in close proximity, represents the weight of tradition. However, acts of defiance, such as the narrator’s secret meetings with Layli, symbolize the push for modernity. Asadollah Mirza’s mentorship of the narrator introduces progressive ideas. It offers an alternative to Uncle Napoleon’s rigid worldview. This tension reflects Iran’s own cultural transition during the mid-20th century, as it grappled with the challenges of modernization while preserving its heritage.

Pezeshkzad’s use of satire amplifies the novel’s themes as well as allows it to critique societal flaws without alienating its audience. Uncle Napoleon’s exaggerated delusions and the family’s melodramatic interactions highlight the absurdity of societal norms. The humor humanizes the characters and makes their flaws relatable and their struggles endearing. Uncle Napoleon’s fixation on military tactics, described by the narrator as “his theater of war”, represents the balance between humor and critique. The novel’s enduring popularity in Iran is a testament to its ability to engage with sensitive topics through laughter.

Overall, in My Uncle Napoleon, Pezeshkzad masterfully blends humor, romance, and social commentary to create a narrative that is both deeply personal and universally resonant. Through its exploration of love, paranoia, and power, the novel critiques the constraints of tradition while celebrating the complexities of human relationships. Pezeshkzad’s vivid characters and sharp wit continue to captivate readers. He offers a lens through which to view not only Iranian society but also universal human experiences. In its blend of satire and sincerity, My Uncle Napoleon remains a testament to the power of literature to entertain, critique, and inspire.

**********************************

Pezeshkzad, Iraj. My Uncle Napoleon. Translated by Dick Davis, Mage Publishers, 1996.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment