Mapping Power and Meaning

An Analytical Review of Building Theory in Political Communication

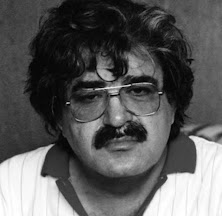

Reza Shirmarz

The landscape of political communication is increasingly fragmented, dynamic, and multi-directional. Amid this complexity, Gadi Wolfsfeld, Tamir Sheafer, and Scott Althaus’s Building Theory in Political Communication (2022) emerges as a crucial intervention, and aims to unify disparate strands of research and theorizing through their Politics-Media-Politics (PMP) approach. Far from proposing a predictive model, the authors offer a flexible, comparative, and cumulative framework that maps how political contexts shape media, how media selectively transform content, and how this reshaped output loops back to influence politics. This analytical article critically engages with the book’s central propositions. It explores its conceptual foundations, applicability across regimes, and implications for future research. It argues that while the PMP model offers a highly useful heuristic, its strength lies in its modesty: it resists grand theorizing and instead encourages systematic, grounded theorization rooted in political realities.

At the heart of the PMP framework lies the claim that politics comes before media. This challenges longstanding assumptions in media-centric research that media possess autonomous agenda-setting power. The authors insist that media systems are first and foremost shaped by the political institutions, norms, and conditions in which they operate. This "politics first" proposition reorients the causal arrow and corrects what the authors see as an imbalance in the literature. The implication is clear: research that treats media systems as independent variables must account for the political ecosystem that undergirds them. For example, a state with concentrated media ownership, weak legal protections, or repressive surveillance regimes will inevitably shape what counts as "newsworthy," regardless of the autonomy of journalists. Wolfsfeld et al. provide cross-national and historical evidence to support this claim. They suggest that media freedom and function must always be situated within political constraints.

However, this positioning may risk overstating the subordination of media systems. In liberal democracies with pluralistic media, journalistic culture and market pressures often resist political control. While the PMP model acknowledges this through its inclusion of cultural and situational dimensions, the weight it gives to structural politics might inadvertently marginalize bottom-up influences such as audience reception and digital media dynamics.

The second major proposition of the PMP model is that media do not simply mirror political events; they select and transform them. Journalists, editors, and media organizations operate under professional routines, economic imperatives, and ideological preferences that filter and reshape political content. This proposition bridges the gap between transmission and constructionist theories. Media do not just deliver facts; they tell stories. The narrative logic of media demands drama, personalization, conflict, and resolution, criteria that are not always in line with political complexity. By emphasizing this, the authors illuminate how media actors serve as powerful gatekeepers and framers. Notably, this argument coordinates with framing theory and agenda-setting research, but the PMP framework embeds these insights into a broader political ecology. Media selection is not random; it is contextually constrained. Yet, here too lies a tension: the line between transformation and distortion is often blurred. In conflict zones, for instance, the simplification of peace processes into binary narratives (success/failure, hero/villain) may do more than reframe reality; it may actively sabotage political progress.

The authors are aware of this danger, particularly in Chapter 3, where they examine the media’s role as potential "peace spoilers." Their careful treatment of the Israeli-Palestinian peace process and American war coverage emphasizes how media can tilt public opinion based on selective visibility. Still, more attention could be given to how non-traditional media, social platforms, influencer networks, and alternative outlets, further complicate the selection-transformation process.

A key strength of the PMP model is its triadic analytical lens: structural, cultural, and situational dimensions. This multidimensionality ensures that no single explanatory variable dominates the analysis.

Structural factors include legal systems, ownership models, and institutional frameworks.

Cultural factors refer to shared values, media norms, and ideological consensus.

Situational factors encompass short-term disruptions, crises, and emergent events.

This typology enables scholars to contextualize media effects in relation to their broader ecosystems. For instance, a structural analysis may explain why public broadcasters behave differently in Sweden than in Turkey; a cultural analysis may clarify why political satire thrives in the U.S. but struggles in China; and a situational lens may show how a scandal reshapes election coverage. The triadic structure is particularly valuable in comparative political communication, as discussed in Chapter 5. By dissecting variance across regimes, the authors show how the same event can yield different media responses depending on contextual configurations. However, the model assumes a certain methodological fluency among researchers. Applying these dimensions requires access to rich data, local expertise, and interdisciplinary tools, resources that are unevenly distributed across academia.

The PMP cycle emphasizes feedback: the media-transformed version of political events is not inert. It loops back into the political system, alters behavior, shapes public opinion, and influences future decisions. This recursive logic is a major advancement over linear models of media influence. For example, election campaigns provide a textbook instance of PMP in motion. Political parties launch strategies to attract media attention (politics → media), journalists transform these events into campaign coverage (selection/transformation), and that coverage affects polling, turnout, and even policy shifts (media → politics). Chapter 2's exploration of horse-race journalism and scandal coverage illustrates this cycle vividly. However, measuring feedback remains a challenge. While agenda-setting and framing effects are well-documented, the causal pathways from media framing to political outcomes are often diffuse. Feedback is difficult to isolate, particularly in digital ecosystems where algorithmic curation and user participation blur the lines between production and reception. Future research might refine this component by incorporating tools from computational communication or behavioral science.

Chapter 6 presents one of the book’s most provocative contributions: using PMP to evaluate media performance across regime types. Traditional approaches tend to assess media quality by press freedom or independence. Wolfsfeld et al. propose a more functional criterion: does the media system contribute to democratic representation and governance? This opens space for evaluating media not merely by how free they are, but by how well they inform, represent, and empower publics. For example, a media system that is technically free but dominated by misinformation may perform worse than a partially constrained one that facilitates pluralistic debate.

In autocratic regimes, the PMP model reveals how media can function as tools of elite reproduction, disinformation, and suppression. Structural controls, such as censorship and ownership laws, combine with cultural taboos and situational crises to produce self-reinforcing media regimes. Yet, as the authors caution, digital platforms now complicate these distinctions. The internet simultaneously empowers dissent and enables surveillance, making the normative evaluation of media more complex than ever.

Perhaps the book’s greatest virtue is its modesty. The authors do not claim to have discovered a universal law or built a formal theory. Instead, they offer a "heuristic", a conceptual map that guides thinking, encourages integration, and fosters comparison. This humility is welcome in a field often split between grand theorizing and empirical fragmentation. The PMP model does not resolve every tension or close every loop, but it invites scholars to theorize with discipline, not dogma. It makes room for both macro- and micro-level insights, from institutional structures to individual media acts.

The book’s clarity and accessibility make it especially suitable for interdisciplinary teaching, graduate seminars, and comparative projects. Yet, its full impact depends on uptake. The authors issue a quiet call to arms: use this framework, test it, adapt it. In doing so, the field may yet become greater than the sum of its parts.

Building Theory in Political Communication offers a rare blend of conceptual rigor, methodological flexibility, and normative reflection. Its core insight, that politics shapes media, which in turn reshapes politics, is not new, but its articulation through the PMP model represents a major advance. By integrating structure, culture, and situation, and by emphasizing feedback and transformation, the book provides a powerful toolset for scholars of media and politics.

While certain challenges remain, especially around measuring feedback, incorporating digital dynamics, and balancing structural determinism with agency, the book’s heuristic approach is precisely what the field needs: a disciplined way of thinking, rather than a rigid theory of everything. As the political communication landscape continues to evolve, Wolfsfeld, Sheafer, and Althaus have given us not just a map, but a compass.

**********************************

Reference

Wolfsfeld, Gadi, Tamir Sheafer, and Scott Althaus. Building Theory in Political Communication: Politics-Media-Politics. Oxford University Press, 2022.

Comments

Post a Comment