|

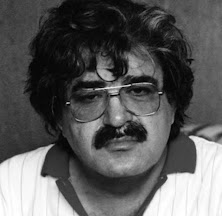

| Anthony Neilson |

Normal, a play by Anthony Neilson, is a gripping psychological drama which explores the infamous case of Peter Kürten, the Düsseldorf Ripper. The story is framed by the experiences of Justus Wehner, Kürten’s defense attorney in the early 1930s, as he confronts the horrors of his client’s actions, the nature of evil, and his own moral boundaries. The play juxtaposes the gruesome, real-life atrocities committed by Kürten with broader questions about human nature, societal structures, and the influence of upbringing on morality. The play begins in 1952 with a reflective Wehner encountering a disturbing arcade machine in a carnival that resurrects his memories of Kürten. This framing device sets the tone for a narrative that spirals back into the lawyer's past, specifically his time defending Kürten in 1931.

|

Normal published by

Bloomsbury in Neilson's

selected Works (1st Vol) |

The play explores several interwoven themes, most notably the nature of evil and insanity. It questions whether malevolence is an inborn trait or a product of trauma and societal failure. While Kürten's defense aims to prove his insanity, he insists on his sanity. He, thereby, challenges conventional ideas of morality and monstrosity. Alongside this, the narrative follows Wehner’s psychological unraveling and reflects society’s own vulnerability to the very darkness it tries to comprehend and control. The play also scrutinizes the role society plays in creating monsters. It uses Kürten’s abusive upbringing to ask whether his crimes were shaped by environment or innate depravity. Furthermore, the complex relationship between Peter Kürten and his wife highlights themes of love, dependency, and control, with her unwavering loyalty raising difficult questions about emotional manipulation, complicity, and the limits of devotion.

Wehner, a young and idealistic lawyer, is eager to prove that Kürten is legally insane. Through his interactions with Kürten, Wehner descends into a chilling psychological confrontation with a man who embodies unrepentant evil yet appears hauntingly charming and intelligent. The encounters peel back the layers of Kürten’s traumatic upbringing, including an abusive household and early exposure to violence, and reveal his calculated manipulations and perverse satisfaction in his crimes. Kürten’s heinous acts range from sexual violence to sadistic murders, all delivered with an unsettlingly calm demeanor. Parallel to Wehner’s relationship with Kürten is the involvement of Frau Kürten, Kürten’s wife. She provides a complex portrait of a woman bound to a monster by twisted love, dependency, and her own troubled past. Despite her awareness of his horrific tendencies, she struggles to reconcile her emotions and continues to stand by him. Wehner becomes increasingly unmoored as he is pulled into the orbit of Kürten’s manipulative charm. Kürten’s philosophical musings about society, morality, and human nature blur the lines between monster and victim. Meanwhile, the details of Kürten’s gruesome murders, such as the killings of children and his depraved acts of necrophilia, are recounted, which make his evil undeniable yet disturbingly fascinating.,%20directed%20by%20Chris%20Loveless.jpg) |

Normal, Bristol (2009),

directed by Chris Loveless |

The play reaches its emotional and psychological climax when Wehner becomes entangled in an affair with Frau Kürten, a union born of shared desperation and emotional ruin. This twisted relationship, subtly orchestrated by Kürten himself, reveals the extent of his manipulative power even as he approaches execution. In the final act, Kürten’s death is portrayed alongside Wehner’s growing self-awareness of his own moral complicity, not only in defending Kürten but in participating in a society that both manufactures and punishes monsters. The epilogue follows Wehner's escape from Nazi Germany and his attempt to rebuild a semblance of normalcy, though he remains haunted by the shadows of his past. The play ends with a haunting reflection on innocence and monstrosity while reminding us that even the most depraved individuals were once children. Overall, Normal is a searing investigation of morality, guilt, and the fragile boundary between civilization and savagery, rendered with Anthony Neilson’s signature blend of stark monologue, dark humor, and surreal theatricality to create a work that is both emotionally wrenching and intellectually unsettling.

|

Smock Alley Boys School, 2016,

directed by Owen Lindsey

|

Now, let's take a look at some of the characters in

Normal. Kürten’s character blurs the line between monstrousness and elegance. He is articulate, charismatic, and disturbingly self-aware, often weaponizing charm to destabilize the moral certainties of others. “You choose to believe that I am insane because you choose not to believe in evil” becomes one of his most chilling declarations, which places the burden of denial on both his lawyer, Wehner, and the audience. His refusal to claim insanity is not ignorance but provocation, suggesting that evil can be rational and even seductive. When he confesses, “There is no place for innocence in this world”, it is less an admission than a diagnosis, evil, in his eyes, is the inevitable outcome of brutality and neglect. Kürten’s disturbing charm is not simply verbal. Neilson stages his murders as performance, most grotesquely in the waltz sequence where Kürten and Wehner rhythmically recite crimes, dancing grotesquely to “February 13th, Rudolf Scheer… A drunken old man reeling through the streets”. That Wehner joins in, “He stood amongst the crowd that watched them carry her away”, signals his progressive moral erosion. Through dance, song, and ritual, Neilson blurs the line between horror and spectacle, which means that society not only tolerates but aestheticizes violence.

,%20directed%20by%20Chris%20Loveless.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment