English and Wish You Were Here by Sanaz Toossi

Unspoken Homeland: Language, Memory, and Migration in Sanaz Toossi’s Plays

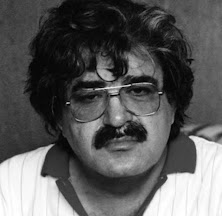

Reza Shirmarz

Sanaz Toossi is an Iranian-American playwright whose work delicately navigates the intersections of language, identity, and exile. Born to Iranian parents in California, Toossi holds an MFA in Playwriting from NYU Tisch and has rapidly emerged as one of the most distinctive voices in contemporary American theatre. Her plays often center on Iranian women negotiating personal and political transformations against the backdrop of historical rupture and diaspora. Toossi’s breakout play English premiered in 2022 to widespread acclaim, earning her the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2023. That same year, she debuted Wish You Were Here, a companion piece in many ways, which deepened her exploration of migration, memory, and female solidarity. With a rare combination of humor, restraint, and emotional clarity, Toossi crafts intimate, character-driven narratives that resonate far beyond their immediate cultural contexts. While I have not yet had the opportunity to see these plays produced, I have had the chance to read them closely. Moved by their emotional depth, formal inventiveness, and sociopolitical urgency, I decided to write about these two innovative works as a way to engage more deeply with their theatrical and thematic resonance.

English

Sanaz Toossi's Pulitzer Prize-winning play English (2022) offers a nuanced examination of identity, displacement, and the fraught relationship between language and selfhood. Set in a TOEFL classroom in Karaj, Iran, in 2008, the play unfolds over six weeks as four students, Goli, Roya, Elham, and Omid, study under the guidance of their teacher, Marjan. Through the formal device of contrasting bolded and non-bolded dialogue (signifying accented English and native Farsi, respectively), Toossi constructs a layered soundscape that interrogates what it means to "have" a language, to lose one, and to shape an identity in the ambiguous terrain between cultures.

The linguistic conceit of English is not merely stylistic. It is central to the play's epistemological inquiry: How do we know who we are when the language we speak shapes how we think, feel, and are perceived? This question recurs in the classroom scenes that blend pedagogical exercises with emotionally volatile conversations. When Goli, the youngest student, says, "English does not want to be poetry like Farsi," she articulates a perceived rigidity in the English language, contrasting it with the lyrical openness of her mother tongue. She adds, "It is like some rice. English is the rice. You take some rice and you make the rice whatever you want." Yet the students' relationships with English are anything but neutral. For Roya, English is a pathway to intergenerational intimacy, "Nader and the wife want I speak in English with Claire," she says of her Canadian granddaughter. Elham, by contrast, views English as an oppressive gatekeeper. Despite having taken the TOEFL five times, she remains embittered: "My accent is a war crime." Her self-loathing is matched by her competitiveness, especially toward Omid, whom she suspects of downplaying his fluency. When Omid is revealed to be a U.S. citizen with a passport and an American upbringing, Elham accuses him of having committed a betrayal, not just of the class but of a shared struggle.

Elham's outbursts, "You tell me, Marjan, that we are improving the accent and the truth hurts but sorrysorry Goli people hear your accent and they go oh my god it is so funny you are so stupid", embody a brutal internalization of linguistic discrimination. Here, Toossi critiques not just the West's valuation of "native" accents, but how those standards infiltrate and corrode communal solidarity within marginalized communities. Marjan, the teacher, is herself a complex figure, caught between empathy and authority. Having lived in Manchester for nine years, she adopted "Mary" as a more acceptable English name. She confesses: "When I came back here, I didn’t know what to answer to." Her pedagogy is not simply about grammar; it becomes an ethics of memory and aspiration. In one moment of deep vulnerability, she tells Omid, "Sometimes I think you can only speak one language. You can know two, but…" Indeed, much of English is structured around failed or incomplete communication. The show-and-tell scenes, games, and listening exercises reveal more about the characters' internal states than any grammar test could. Roya struggles to understand her son’s voicemail, noting the emotional difference between his English and Farsi: "Do you hear how much more soft he is in his mother tongue? He forget in English but in Farsi he remember."

The epilogue is particularly striking: Elham returns, having scored a 99 on the TOEFL. She confronts Marjan, saying, "I am more than proficient. I am it says superior." Yet the triumph is bittersweet. "No one hates this language more than I hate," she declares, before offering a complex self-assertion: "Okay I know what I sound like. I hear my voice too. But I am hearing myself. I hear my sister and traffic in the morning and my chemistry teacher from in the high school. I hear my home. What do you hear?" The play ends not with resolution, but with a lingering question about the cost of assimilation. Toossi doesn’t offer closure because the immigrant condition rarely provides it. English is ultimately not about mastering a foreign language, but about the haunting impossibility of ever speaking without echo. In its quiet, devastating final moments, it suggests that language is not just a tool for communication, it is a geography of longing, loss, and becoming.

Wish You Were Here

Sanaz Toossi's Wish You Were Here (2022) is a haunting, often darkly comic meditation on female friendship, exile, and national upheaval. Spanning thirteen years, 1978 to 1991, and set in Karaj, Iran, the play charts the slow dissolution of a once-tight circle of women through the mechanisms of war, revolution, and emigration. At its core, the play is about what remains when those closest to us disappear, not only physically but emotionally, linguistically, and ideologically.

.jpeg)

Language in Wish You Were Here functions as both bridge and chasm. The women often speak in unison early in the play, especially during weddings, forming a choral unity. But as the years pass and English replaces Farsi for those abroad, language becomes a site of alienation. When Nazanin listens to her son’s voicemail in English, she notes, "He forget in English but in Farsi he remember." Perhaps the most heart-wrenching moment occurs when Nazanin receives a call from Rana in 1991. Rana, pregnant and living in California, declares, "My daughter will never know what an IR-2 is... she will never know how fast this Earth can spin underneath you." Her words echo the thematic trauma of displacement and identity effacement. Rana seeks to protect her child by erasing any connection to the chaos she left behind. Nazanin, however, is left with the residue of everyone else's escape.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment