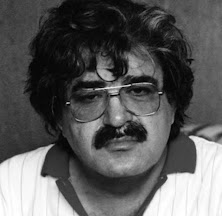

Wole Soyinka

Between Myth and Power: The Dialectics of Tragedy and Satire in Wole Soyinka’s Dramatic Imagination

Reza Shirmarz

As Biodun Jeyifo observes, Soyinka’s theater resists both Eurocentric formalism and nativist romanticism. He opts instead for “a tragic vision which is rooted in ritual archetypes yet open to modern historical consciousness” (Jeyifo). Soyinka’s life is deeply imbricated with the political and cultural upheavals that shaped Nigeria’s emergence from colonialism. Born in 1934 in Abeokuta, Western Nigeria, he was raised in a household that combined Yoruba religious traditions with Christian education. His education at the University of Leeds and exposure to European literature and philosophy sharpened his awareness of both cultural synthesis and colonial alienation. On returning to Nigeria, he began a long career of writing and political engagement, interrupted by arrest and solitary confinement during the Nigerian Civil War. These experiences generated a unique dramaturgy of resistance: one that critiques systems of power not only through narrative, but through the very structure and rhythm of performance.

|

| The Strong Breed by Wole Soyinka |

This tragic vision reaches its most metaphysically charged expression in Death and the King’s Horseman. Often misread as a play about a “clash of cultures” between the Yoruba ritual world and British colonial authority, the play is more accurately a meditation on metaphysical failure. Elesin, the titular horseman, fails to complete his ritual suicide at the death of the king, and therefore, severs the cosmic chain of continuity between the dead and the living. When his son Olunde, educated in England, hears of his father’s failure, he accuses him: “You have lost everything. You have thrown the world down into the abyss”. Olunde’s self-sacrifice becomes the true tragic act while underscoring Soyinka’s belief in the continuity between personal responsibility and metaphysical balance. As Obi Maduakor affirms, “Soyinka’s heroes do not seek justice or revenge; they bear the burden of cosmic reintegration” (Maduakor). Yet Soyinka’s theatre does not dwell solely in tragic solemnity. Parallel to his mytho-tragic works is a powerful current of political satire, often irreverent, grotesque, and farcical. Plays such as The Trials of Brother Jero, Jero’s Metamorphosis, Kongi’s Harvest, and A Play of Giants expose the hypocrisies of religion, nationalism, and statecraft. In The Trials of Brother Jero, the eponymous character, a beachside preacher, manipulates his followers with exaggerated piety. “I am a prophet. A prophet by birth and by inclination,” he declares as conning people into giving him money and loyalty. Soyinka’s satirical impulse functions here as a moral exorcism and exposes the commodification of spirituality in the wake of colonialism and its discontents.

|

| Death and the King’s Horseman |

Beyond structure and genre, Soyinka’s language itself is a site of radical tension. His plays are marked by poetic density, cryptic symbolism, and linguistic hybridity. Critics have debated the opacity of his writing, with some accusing him of elitism. Jeyifo, however, defends Soyinka’s style as “a purposeful estrangement.” He notes that his complex idiom is part of an ethical project: “to resist the commodification of language and the reduction of African experience to consumable form” (Jeyifo). Indeed, the stylistic difficulty of works like The Road, where the Professor muses endlessly on the “Word” as the key to death’s mystery, reflects Soyinka’s metaphysical ambitions. “The Word is missing,” Professor exclaims, “it is in the throat of silence”. In such moments, language collapses under the weight of philosophical yearning, and the play becomes a ritual of epistemic frustration.

His drama is not easily legible within Western frameworks of realism or didactic theatre. Nor does it fully align with African socialist realism. Instead, it speaks from a liminal space, a fourth stage, where memory, myth, and modernity contend for meaning. As such, Soyinka remains a singular figure in world drama, not because he synthesizes traditions, but because he agitates them. His plays force readers and audiences into ethical confrontation, not resolution; into metaphysical unease, not comfort. In an era when theatre is often reduced to either entertainment or ideological posturing, Soyinka’s dramaturgy reminds us of the deeper function of performance: to re-enter history through ritual, to interrogate the present through myth, and to imagine a world where sacrifice is not absurd but necessary. His work, ultimately, is a sustained inquiry into how art can shape consciousness in the face of tyranny and forgetting.

References

Gibbs, James. Wole Soyinka. Grove Press Modern Dramatists, 1986.

Jeyifo, Biodun. Wole Soyinka: Politics, Poetics, and Postcolonialism. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Maduakor, Obi. Wole Soyinka: An Introduction to His Writings. Garland Publishing, 1986.

Msiska, Mpalive-Hangson. Wole Soyinka. Writers and Their Work, Northcote House Publishers, 2007.

Soyinka, Wole. Collected Plays 1. Oxford University Press, 1973.

Soyinka, Wole. Collected Plays 2. Oxford University Press, 1974.

Soyinka, Wole. Collected Plays 3. Oxford University Press, 1994.

Soyinka, Wole. Myth, Literature and the African World. Cambridge University Press, 1976.

Comments

Post a Comment