Art in the Era of Digitalization

Its Originality and Universality

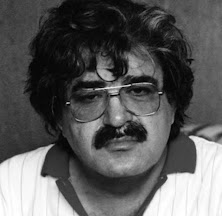

Reza Shirmarz

First and foremost, the process of digitalization has boosted all the elements to which Ellen Dissanayake referred in her definition of art. Additionally, the undeniable fact is that the process of digitization has a formal effect on the works of art, but the originality is still there shining as before not only for the elite but also for the public audiences. The fabric of the digitalized society receive the original piece of art, individuate it and take part in the scintillating performance of the artist. The creator and the consumers of artwork together in the digital era and the receivers of art enjoy the same "mutual ecstasy" as the artists through a process of "vision and revision" (Davis, 1995). This seems to be the era of Oneself as Another. The digitalization of art has converted the mental omnipresence of a work of art into visible and visual ubiquitousness where cognito ergo sum and therefore artistic solipsism have been eschewed by the globally interconnected networks of the performers (artists & audiences). This precise visual omnipresence could be upgraded or degraded while being copied and pasted by any random member of the universal audience, but the point is not whether this might devaluate the piece of art itself, since it definitely cannot, the question is how universally could a work of art be observed and even changed into a new form which is the output of the collaboration of the two sides of a coin called art. The digital era has given us the chance to reproduce art through the synergy coming from the original creators and their endless audiences.

First and foremost, the process of digitalization has boosted all the elements to which Ellen Dissanayake referred in her definition of art. Additionally, the undeniable fact is that the process of digitization has a formal effect on the works of art, but the originality is still there shining as before not only for the elite but also for the public audiences. The fabric of the digitalized society receive the original piece of art, individuate it and take part in the scintillating performance of the artist. The creator and the consumers of artwork together in the digital era and the receivers of art enjoy the same "mutual ecstasy" as the artists through a process of "vision and revision" (Davis, 1995). This seems to be the era of Oneself as Another. The digitalization of art has converted the mental omnipresence of a work of art into visible and visual ubiquitousness where cognito ergo sum and therefore artistic solipsism have been eschewed by the globally interconnected networks of the performers (artists & audiences). This precise visual omnipresence could be upgraded or degraded while being copied and pasted by any random member of the universal audience, but the point is not whether this might devaluate the piece of art itself, since it definitely cannot, the question is how universally could a work of art be observed and even changed into a new form which is the output of the collaboration of the two sides of a coin called art. The digital era has given us the chance to reproduce art through the synergy coming from the original creators and their endless audiences.

In the meantime, universality conveys some sort of absolutism. Universal pieces of art are supposed to be received and understood by all societies and human beings. But to what extent could this notion be reliable? Do all the residents of our planets have a true and precise understanding of a well-known artwork like Mona Lisa? Or it seems more reasonable to say that every single audience of every piece of art receives it differently due to their cultural background and unique mentality. The global digitalization has provided the audiences of artworks, wherever they reside or at any time, with the capability of sharing their unique derivatives of an original work based on their cultural context and individual mindset as well as the level of technological advancement in their particular geography. Digitalization has caused faster and more effective universalization. Concurrently, the existing works of art have had the opportunity to be multiplied into uncountable pieces. Adaptability of art on a global scale is another output of the current digitalization process.

The unprecedented development of reciprocal communication and the boundless, countless and unending interaction between the two groups of performers, i.e. artists and their online audiences (viewers, buyers, promoters, participants, etc.), in the digital era has profoundly assisted the phenomenon of art to get elevated to higher levels of creative visual participation, which might have boosted up the concept of art decentralization, its deconstruction, reproducibility, repeatability as well as its universality. This is how, according to Davis (1995), the art consumers and experts now have the possibility of producing a "post-original original." This is "when copying is not copying" (Donahue, 2008) and refers to "the dynamic nature of common knowledge " (England, 2008), creativity and self-expression.

References

Davis, D. (1995), The Work of Art in the Age of Digital Reproduction (An Evolving Thesis: 1991-1995), Leonardo, 1995, Vol. 28, No. 5, pp. 381-386.

Dissanayake, E. (2008), The Universality of the Arts in Human Life, in Understanding the Arts and Creative Sector in the United States, J. M. Cherbo, R. A. Stewart & M. J. Wyszomirski (eds), New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London, Rutgers University Press.

Donahue, Ch. (2008), When Copying is Not Copying: Plagiarism and French Composition Scholarship, from Originality, Imitation & Plagiarism: Teaching Writing in the Digital Age, Caroline E. & Martha V. (Eds.), USA, The University of Michigan Press.

England, A. (2008), The Dynamic Nature of Common Knowledge, from Originality, Imitation & Plagiarism: Teaching Writing in the Digital Age, Caroline E. & Martha V. (Eds.), USA, The University of Michigan Press.

Kilgore, R. (May, 1954), The Universality of Art, The Phi Delta Kappan, Vol. 35, No. 8, pp. 303-305.

Pap, A. (Sep, 1943), On the Meaning of Universality, The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 40, No. 19, pp. 505-514.

Very interesting. Thanks for sharing this. Good luck

ReplyDeleteThanks for reading it. Cheers!

DeleteAwesome to-the-point piece of writing. Nice references. Thanks a lot.

ReplyDeleteI appreciate your comment, William. Wishes!

Delete