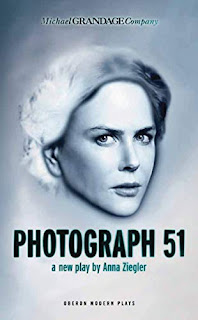

Photograph 51 by Anna Ziegler

Reza Shirmarz

|

| Anna Ziegler |

Photograph 51 by Anna Ziegler is about the real-life drama surrounding the discovery of the DNA double helix structure. The playwright focuses particularly on Rosalind Franklin, a talented scientist whose pivotal contributions were largely overlooked at the time. The play centers on the race among scientists to decipher the structure of DNA in the early 1950s. Franklin is depicted as intensely dedicated to her work and highly protective of her research methods and data. The play opens with her arriving at King’s College where she faces subtle and overt sexism from her male colleagues, particularly Wilkins, who initially misunderstands her role and expects her to be his assistant. Franklin’s relationship with Wilkins is fraught with miscommunication and tension, marked by conflicting personalities and expectations. One of the play's central symbols, Photograph 51, is an X-ray image captured by Franklin that provides key insights into the structure of DNA. However, her unwillingness to work collaboratively and the possessiveness she feels over her research ultimately distance her from her colleagues. This tension leads Wilkins to show Photograph 51 to Watson and Crick who use it to build their successful double helix model.

Through Franklin’s story, Photograph 51 examines themes of scientific ambition, gender discrimination, and the personal costs of devotion to one’s work. The play suggests that Franklin’s isolation and refusal to collaborate might have hindered her chance to be recognized for the discovery. Ziegler dramatizes Franklin's inner conflicts and captures her determination as well as frustrations with the academic environment, and the pressures faced by women in science. Photograph 51 reflects on Franklin's legacy and highlights how her contributions to science were essential yet overshadowed by the more celebrated accomplishments of her male peers. It underscores the importance of recognition and collaboration in scientific discoveries, with Franklin portrayed as both a victim of her time and a formidable and uncompromising scientist.

Anna Ziegler’s playwriting style in Photograph 51 is marked by a poetic yet direct approach that allows her to delve deeply into the complex inner lives of her characters. She manages to weave an engaging narrative around scientific discovery. The play focuses not just on events but on the emotions, motivations, and internal conflicts driving those involved in the race to discover the structure of DNA. Ziegler’s style combines historical fiction with nuanced character study. She manages to interlace dialogue with introspective monologues and a non-linear structure that lends an almost dreamlike quality to the narrative. One of the defining characteristics of Ziegler’s style in Photograph 51 is her use of fragmented and overlapping dialogue, which reflects the overlapping ambitions, perspectives, and misunderstandings between the characters. Conversations are often interrupted or overlapped with the inner thoughts of other characters. This creates a sense of tension and unresolved conflict that underscores the play’s themes of rivalry, isolation, and the quest for recognition. This layering of dialogue with internal monologues allows Ziegler to shift seamlessly between objective events and subjective experiences and draws the audience into the emotional undercurrents that shape the characters' interactions. Moreover, Ziegler’s characterizations are also deeply nuanced, with each character embodying both their historical role and a broader archetype in the competitive world of science.

.jpeg) |

| Nicole Kidman as Rosalind Franklin |

Rosalind Character

|

In Photograph 51, Rosalind Franklin is portrayed as a complex, brilliant, and determined scientist whose pioneering contributions to the discovery of DNA’s double-helix structure went largely unacknowledged during her lifetime. Anna Ziegler’s portrayal of Franklin emphasizes both her remarkable intellect and the profound isolation she endures, shaped by both her uncompromising approach to work and the gendered expectations of her era. Franklin emerges as both a tragic and admirable figure, a blend of resilience, vulnerability, and fierce independence that challenges societal norms and complicates her relationships. Franklin is introduced as a scientist with extraordinary focus and discipline, someone whose primary devotion lies in her meticulous work with X-ray crystallography. She is drawn to the elegance and precision of science. She sees beauty in crystalline structures and the order that they represent. This perspective fuels her insistence on accuracy and evidence over speculation,. This sets her apart from her contemporaries, especially James Watson and Francis Crick, who rely more heavily on hypothesis and collaborative experimentation. Franklin’s methodical and independent approach reflects her character’s deeper need for control in a world that often undermines her authority and capabilities, both as a scientist and as a woman. Franklin’s interactions with Maurice Wilkins underscore much of her internal conflict. Though they are ostensibly partners in research, they constantly clash due to Wilkins’ expectation that Franklin will be his subordinate and her expectation to be treated as an equal. Franklin’s reluctance to collaborate and her resistance to Wilkins’ condescending attitude reveal the pride she takes in her work but also reflect her profound distrust of others, a distrust that may stem from years of struggling against biases. Her unwillingness to compromise or soften her approach also isolates her within her own lab; she avoids forming personal connections with her colleagues. She is scared that any intimacy might be misconstrued as weakness or dependency. Ziegler uses Franklin’s relationship with Wilkins as a focal point to highlight how Franklin’s isolation is partly self-imposed but also largely a product of the sexist structures around her, which limit her opportunities and marginalize her voice.

A significant aspect of Franklin’s character is her struggle for recognition, which is symbolized in the play by Photograph 51 itself, the X-ray image she captured, which provided critical evidence for the double-helix structure. Ziegler imbues this photograph with dual meaning: it represents Franklin’s scientific legacy but also the invisibility she endures, as her work is taken without acknowledgment by Watson and Crick. Franklin’s inability to claim her own work in a collaborative or public setting reflects the difficult position of women in science at the time, where their contributions were often overshadowed or outright claimed by their male peers. This dynamic is painfully illustrated when Wilkins shares Photograph 51 with Watson and Crick, an act that undermines Franklin’s control over her research and her place in history. Here, Ziegler highlights Franklin’s tragic flaw: her lack of trust in others prevents her from seeking allies who might have helped her secure her place in the race to DNA’s discovery.

Despite her challenges, Franklin is portrayed as courageous and principled. She is deeply devoted to her work, not for fame or glory, but for the pursuit of truth and understanding. Her dedication to precision and truth-seeking makes her resistant to shortcuts or models that oversimplify reality. However, this same trait ultimately limits her ability to compete in the race, as she is unwilling to speculate without evidence. In this way, Franklin’s tragedy is not just her exclusion from scientific recognition but also her internal conflict between a love for truth and the demands of a competitive, often ruthless scientific community.

Language

Language in Photograph 51 shapes character dynamics, reflects historical context, and underscores thematic elements of isolation, ambition, and gender disparity. Ziegler’s choice of language in dialogue, monologue, and symbolic references lends the play a distinct emotional depth and creates a nuanced atmosphere of competition, tension, and unspoken grievances within the scientific community of the 1950s. Through careful manipulation of linguistic features like tone, conversational structure, and metaphor, Ziegler articulates not only the scientific ambitions of her characters but also their unarticulated desires, biases, and vulnerabilities. One of the most striking linguistic features in Photograph 51 is the fragmented, often overlapping dialogue that mirrors the competitive nature of the scientific race for the DNA double helix structure. Ziegler frequently breaks up and overlaps conversations, particularly between Rosalind Franklin and her male colleagues. The interrupted exchanges reflect the lack of mutual understanding and respect, especially between Franklin and Maurice Wilkins. For example, Wilkins often attempts to assert control or bond superficially, while Franklin’s curt and precise responses reinforce her unwillingness to submit to his expectations. This linguistic fragmentation creates a sense of tension and highlights the clash between Franklin’s need for professional respect and Wilkins’ condescending, dismissive manner which accentuates the broader gender-based power imbalance of the time.

Ziegler’s use of conversational implicature, the unspoken assumptions and meanings embedded within dialogues, also plays a significant role in character interactions. Rosalind Franklin, for instance, often uses direct and literal language that is devoid of pleasantries or softening devices, which contrasts sharply with the more indirect language of her male colleagues. This difference in conversational style can be read as a reflection of Franklin’s internalized expectation to act professionally and avoid perceived “feminine” behaviors to gain respect. However, her directness also isolates her, as her colleagues interpret it as coldness or even arrogance. Her linguistic style thereby emphasizes both her resilience and the gender-based constraints of her environment, while Wilkins and others’ indirect, sometimes patronizing language reinforces their subtle condescension.

Lastly, Ziegler’s selective use of humor and irony serves as a linguistic tool that further defines relationships and power dynamics. Watson and Crick’s ironic, often derogatory humor reflects their casual disregard for Franklin supporting the idea of sexism that permeates the play. Their irreverent language contrasts with Franklin’s serious tone and therefore, highlights not only their differing priorities but also the culture of sexism and intellectual elitism that marginalized her contributions. The language of irony in the play stresses the tragic aspect of Franklin’s character: she is isolated by her devotion to precision and truth, while her male peers use humor to cement camaraderie and discredit her in her absence. In conclusion, the language in Photograph 51 operates on multiple levels to deepen character interactions, emphasize the thematic elements of ambition and recognition, and critique the gendered expectations within scientific communities. Through fragmented dialogue, metaphor-rich monologues, variations in register, and the use of irony, Anna Ziegler creates a linguistically layered narrative that captures both the scientific fervor and personal stakes of the DNA discovery.

Dramatic Space

Comments

Post a Comment