An Iranian Absurdist Playwright

By Reza Shirmarz

Nosratollah Navidi (1930-1988) was born in Vey Nesar, a village in Sanandaj, into a feudal family that owned a citadel. As noted by Naseh Kamgari (2022), the ruins of this citadel still stand untouched in the village of Soorcheh. Navidi completed military academy and earned a BA in Persian Literature before the 1953 coup d'etat. His plays and stories soon gained him national recognition. In 1967, he published Two Snakes, a collection of ten stories. Other notable works from pre-revolutionary Iran include Two Mothers, Bazar, The Man and the Guest, and Hunger for Miracle. Several of Navidi’s plays, including A Dog at Harvest (directed by Abbas Javanmard), A Man with Two Trays (directed by Manouchehr Anvar and published in a literary magazine), and Sustenance (directed by Jafar Vali), showcased his dramatic talent. Other plays, such as Night, Tractor, The Servant and Master, Tamaroozha (directed by Abbas Javanmard), and New Zeal, further cemented his reputation. Some of Navidi’s plays remain unpublished and unknown, even to Iran’s cultural elite.

Navidi’s plays often served as sociopolitical critiques, characterized by a straightforward and accessible tone. Some critics, including Kamgari, suggest that "simplicity and clarity are two elements that have made his dramatic weaknesses less visible for the audience" (Kamgari, p. 2). His anti-government stance and criticism of the flawed agricultural policies, along with his focus on issues like "starvation and unemployment" (ibid, p. 2), led to his interrogation by SAVAK in 1974. Despite his opposition to the monarchy, Navidi was awarded for his play A Dog at Harvest at the Shiraz Festival of Arts in 1969. In 1977, he resigned from his position at the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults as revolutionary forces began to reshape Iran. Isolated in post-revolutionary Iran, Navidi eventually moved to Germany, where he passed away from lung cancer after a brief hospitalization. Although he was a prominent Iranian playwright in the 1960s and 1970s, there is little written about him in both contemporary Iranian academia and international scholarship.

A Dog at Harvest

(1968)

|

Ali Nasirian (left as Heydar) and Azar Faqr

(as Robabeh) in A Dog at Harvest directed by

Abbas Javanmard |

This is a three-scene play directed by Abbas Javanmard in Tehran. At nightfall, a weary but determined farmer named Heydar crouches beside his freshly harvested wheat. With quick, secretive glances, he digs a deep hole, burying a significant portion of his harvest to shield it from those who might take it. The atmosphere is tense and quiet, his actions driven by a need he barely acknowledges. In the second scene, dawn breaks over Heydar’s modest home. He and his wife, Robabeh, gather their children. One of the youngest, with hungry eyes and an empty stomach, asks for a watermelon. Heydar hands the child a handful of wheat—enough to trade with a neighbor for the prized fruit. The children run off, but before Heydar and Robabeh can share a moment of peace, a group of Dervishes arrives, their voices raised in chants and invocations. They demand their share of the harvest, invoking the Prophet and Imams. Robabeh’s face hardens, and with resolute defiance, she rebuffs the Dervishes one by one, forcing them to retreat empty-handed. As she breathes a sigh of relief, Mosayyeb, the village’s wealthy and rotund shopkeeper, appears, casting his imposing shadow over the family. He demands payment from Heydar’s harvest for goods previously bought on credit. Robabeh protests passionately, pleading for more time. Her voice, filled with desperation, echoes her determination to protect their children from starvation. Mosayyeb, however, remains unmoved, pressing his claim. Heydar attempts to calm Robabeh, but her fury is unstoppable—until Heydar, in a moment of frustration, strikes her. Robabeh falls, clutching her face in pain, as Mosayyeb takes half their hard-earned harvest and departs. After Mosayyeb leaves, Heydar kneels beside his injured wife, a glimmer of hope lighting his face. He reveals the hidden stash of wheat he had buried earlier, showing Robabeh that all is not lost. Through her pain, a faint smile appears on her face. Looking at the buried wheat, she reflects on their hardships, calling herself a “dog at harvest,” yet clinging to the fragile hope that they might endure this difficult season.

|

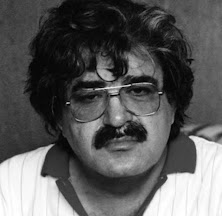

Reza Karam-Rezayi in

A Dog at Harvest |

Text Analysis. Rural poverty and class conflict lie at the heart of A Dog at Harvest, as Nosratollah Navidi crafts a stark portrayal of inequality in rural Iran. The gap between the rich and the poor is a recurring theme in Navidi’s work, revealing how social divides are perpetuated through intertwined forces of economic disparity, religious authority, and political power. This chasm, as Navidi suggests, is not simply economic but also stems from metaphysical ideologies and the influence of governing powers, which together deepen the struggles of the rural poor. The arrival of the three Dervishes, intent on claiming a share of Heydar's harvest, brings religion into the play as a tool of control. They are not simply religious figures but represent how religious authorities, aligned with power structures, impose a moral obligation on the poor to give even from their own scarcity. This use of religion to extract labor or goods from the already impoverished highlights a disturbing collusion: religious and political authorities can coerce compliance under the guise of spiritual duty. In Navidi’s play, these Dervishes embody a systemic religiosity that places economic and social control in the hands of those in power, exploiting belief to subjugate rather than uplift. In contrast, Robabeh emerges as a striking figure of resistance. She represents a modern, uniquely Iranian archetype of the rebellious woman—a defiance not drawn from the tragic vengeance of figures like Medea or the ambition of Lady Macbeth but from a fierce, grounded desire to protect her family’s survival. Robabeh’s rebellion is not one of power-hungry manipulation or mythic retaliation; instead, it is marked by a raw determination to shield her children and her home from the encroachments of unjust religious and social impositions. Through her defiance, she implicitly challenges patriarchal authority and the religious mandates that strip her family of their meager security. Navidi thus offers a subtle feminist critique through Robabeh, positioning her as an anti-religious symbol who stands against the violence—both verbal and physical—that targets women. She becomes a voice against the entrenched norms that seek to subdue her, whether they arise from religious figures, wealthier villagers, or even her own husband. Robabeh’s resistance is particularly significant in the Iranian context, where defiance against the expectations placed on women carries unique implications. Her character underscores a larger tension between modern resistance and traditional, often repressive, structures. In rejecting the imposition of religious control over her life, Robabeh also echoes a broader social resistance against the coercive blending of religion with power, suggesting that survival itself becomes an act of defiance in a society that pressures the weak into submission.Tamaroozha

(1970)

Blessed be the gambler who gambled away all he had, so was left with nothing but the desire for another gamble (Rumi, Gazal No. 1085)

In this one-act play directed by Abbas Javanmard in Tehran, titled Tamaroozha (meaning “those who are full of regret” in Kurdish), Navidi delves into the struggles of Morad, a destitute farmer desperate to improve his family’s situation. The play opens with Morad, faced with extreme poverty, deciding to take a risk: he plans to trade the last of their wheat supply for molasses—a sweet syrup made from condensed fruit juice, typically grape—hoping to sell it at a profit in the village center. However, his wife, Kobra, strongly opposes this plan, fearing they’ll lose their essential food supply for an uncertain gain. Against her wishes, Morad goes ahead, determined to provide a better life for his family. At the village center, Morad encounters Mosayyeb, a local shopkeeper from the wealthier part of the village, who derides him, saying, “Molasses belongs to the wretched…” Morad, however, tries to brush off the insult and attract potential buyers. A group of women approach, seemingly interested in his molasses, but in the midst of negotiations, a dead mouse falls from his leather bag into a customer’s bowl of syrup, destroying his chances for profit. Horrified, the women refuse to buy, recoiling in disgust and calling it nejasat, or religious impurity. Morad, panicked, tries to persuade them that it’s not a mouse but merely sediment, a sign of the syrup’s quality. Yet the women are unmoved and flee in horror. Desperate, Morad is even willing to swallow the mouse himself to prove his product’s worth, but the village magistrate intervenes, dismissing the molasses as najis (impure) and disposes of it, ignoring Morad’s pleas to return his only remaining asset. In the background, funeral prayers echo, chanting, “God is merciful... God is benevolent,” as the village mourns a recently deceased crippled man. As hope slips away, Morad, devastated, turns on the villagers, declaring, “You godless people,” and decides to leave the village entirely in search of a new beginning elsewhere. As he departs, Mosayyeb emerges from his shop, saying prayers as he heads to the funeral. Kobra and their son, Hasani, appear. In a fleeting, silent exchange, Morad and Kobra look at each other. The stage fades to black, leaving their future uncertain, yet underscoring the harsh realities of rural life and the relentless grip of poverty and social stigma.

Text Analysis. Nosratollah Navidi, himself a farmer and rancher, brings an authentic understanding of rural Iranian life under the Shahs to his work. His deep familiarity with these challenges allows him to portray his characters, particularly the farmer and his wife, with precision and respect, rooted in the simplicity of rural existence. Navidi’s writing is stripped of intellectual flourish, focusing instead on the everyday struggles of common people, which has earned him the title of “People’s Playwright.” His dramas, though often absurdist, remain accessible to the average theatergoer, devoid of the dense structures or stylized characterizations seen in works by playwrights like Akbar Radi, whose play Declination offers a more formally complex approach to dialogue and character development. In Tamaroozha, Navidi explores four central issues: class conflict, religiosity, abuse of power, and thanatophilia, or the social fascination with death. First, Navidi offers a grounded depiction of class conflict within Iranian society. The play shows the dominance of the wealthy and the ongoing struggle for survival among the working class. Through the character of Morad, Navidi brings this disparity to light. Morad's own words underscore this sense of exclusion and deprivation: “We’re nobody… not even a part of the human community… We haven’t got any meat to eat… and you can’t have only dry bread.” His lines reveal the internalized sense of worthlessness and resignation that define the working-class experience under oppressive class hierarchies. The theme of religiosity in Tamaroozha also reflects the powerful impact of religious laws and beliefs on rural communities. The concept of najis, or religious impurity, becomes a central force in Morad’s downfall when a dead mouse—though its actual presence is ambiguous—falls from his bag into his customer’s bowl, rendering his goods religiously impure. Navidi uses this moment to critique how strict religious interpretations can destroy livelihoods based on mere perception, regardless of actual evidence. Navidi further examines power abuse through the figure of the village magistrate, who embodies a system that uses Sharia law to enforce class distinctions and deprive the lower classes of basic security. The magistrate’s authority is not rooted in justice but rather in maintaining social hierarchy, marginalizing characters like Morad who lack the means to challenge these powerful systems. Finally, the play delves into the theme of thanatophilia, or a preoccupation with death, which permeates the village society. Navidi portrays a culture steeped in a fascination with mortality, an attitude fostered by religious and sociopolitical forces that normalize suffering and glorify death. Morad’s decision not to participate in the village funeral procession symbolizes his rejection of this ingrained death-centered mentality. While the villagers, young and old alike, join the funeral eagerly, Morad stands apart, signaling his resistance to a worldview that has kept his community submissive and destitute. Through Tamaroozha, Navidi provides a piercing analysis of the forces that trap the rural poor—religion, class structure, and power abuse—while also examining how these forces shape the collective psyche. His work offers an unflinching look at the toll these societal structures take on individuals like Morad, who, despite moments of rebellion, ultimately remain ensnared by the very systems they oppose.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References

Kamgari, N. (2022). A Dog at Harvest and Some other Plays by Nosratollah Navidi, Edited by Naseh Kamgari, Tehran, Yekshanbeh Publication.

Shayanfar, Z. (May, 2006). A Reading of "A Dog at Harvest", Iran Theater, Retrieved from https://theater.ir/fa/1710

Hope to have the translation of his plays soon. Sounds pretty creative and avant-garde. Thanks.

ReplyDelete