To be open-minded & open-hearted

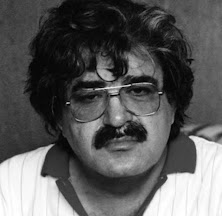

An Interview with Andreas Flourakis:

A contemporary Greek playwright & theater director

by Reza Shirmarz

|

| Andreas Flourakis |

Andreas Flourakis had written a couple of good plays and had received an international recognition for his innovative work when I got to know him. I found him primarily as a creative playwright. He kicked off his directing career as well after some years. I saw some of his performances and really liked his compressed but fully dynamic dramatic world. His plays have been translated into several languages, including English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, German, Turkish, Romanian, etc. as well as performed in several recognized stages on national and international scales. Andreas, has also received several awards such as the UNESCO International Monodrama Award, Writer-in-Residence Award (the Royal Court International Residency), Fulbright Artists Award (US), Eurodrama contest award, etc. Some of his plays are Animal, Blind Faith, Bones, Lassie, Shell, Sea Blue, Ice, Medea Burqa, etc. several of which have been published. He writes poetry and novels as well. I decided to interview him after I sat to watch his Tap Out in a local theater in Athens. Innovative, to-the-point and dynamic like always!

At which point of your life have you faced a phenomenon called theatre? And since when has theatre, especially playwriting, changed into the most serious part of your artistic life?

Back in the early nineties, I made my first contact with the world of theatre through acting. Soon I changed direction and pursued a diploma in cinema. In 1998 I started writing my first full-length play “Antelopes”, which after countless of drafts I finished at the beginning of the new century. “Antelopes” was the starting point of my adventure in playwriting and the beginning of a new era in my creative life.

Why did you choose drama as your main medium as compared to other literary forms?What are main themes of most of your plays?

Thematically, I mainly deal with everyday life, politics and ancient drama.

|

| I WANT A COUNTRY / NEW YORK INTERNATIONAL FRINGE FESTIVAL, 2018. Directed by Lyto Triantafyllidou. |

And in what ways do you come up with your new ideas, characters, and situations?

I feel more inspired during the summer months, when I leave the city and stay close to nature. I usually come up with lots of ideas and situations, but only very few of them come to the finish line.

How important is language in your plays?

In some of my plays, language is determinant. Others rely on situation, action, or other elements that take the lead. A few times, when I felt that the Greek language in a play was intimidating, I wrote in English, a very liberating experience.

What are the characteristics of the language you use in your dramatic works?

Most of the time I use contemporary language, as it works in everyday communication and the media, old and new.

How do you build the relationship between the language, content and the physicality of the characters?

It’s a sort of choreography, I suppose. Language and body exist in direct contact with actors and voices on the stage. When it comes to writing it depends on the play. For example in my polyphonic plays, my characters are a kind of speech agents and not people with a past and a CV. I am mostly interested in the way different speech levels react or introduce performativity situations.

|

| MEDEA BURQA / Epi Kolono Theatre, Athens, Greece, 2014. Directed by Andreas Flourakis. |

You started your career as a playwright. Why did you start, afterwards, to direct your own plays? Are there any particular reasons for that?

It is not well known, but my first theatre directing took place a long time ago, in 2002. Nevertheless playwriting was my thing. There are times when I feel like directing, especially when I have strong images of a play, mine or not. It is a creative gap between writing plays.

This journey is meant to be. Every production follows different routes, so the journey will never be the same. Destination fulfilled.

How far do you think it is artistically and professionally acceptable to direct what you write? Is it a successful experience? How rewarding could it be in your personal view?

Traditionally it’s not unusual for a playwright to direct his own writings. When I direct a play of mine, I forget that I’m the playwright and I deal with it as if it was written by someone else. Obviously, there is no guarantee of success. As any director would agree, I guess, it is always rewarding when you establish a meaningful connection with the audience in a performance.

What do you mean by "a meaningful connection with the audience"? What interaction do you expect between your dramatic work and your audience?Certainly, not a passive one. For example, in one of my monodramas, Tap Out, the character, a boxer, starts threatening the audience, which feels anxious, to say the least. Some guys showed an intention to actually react... This is not uncommon but still it was interesting. I thought I needed a reaction like that, not particularly a physical one, but an intellectual and emotional one. Anyway, there are lots of views about the reactions of the audience nowadays, aren’t they?

|

TAPOUT, Theatre of Odou Kefallinias, Athens, Greece, 2017. Directed by Andreas Flourakis |

How many playwriting trends are there in today’s Greece?

Literally every trend exists. The theatre in Greece has been very vibrant for the last several decades. Hundreds of productions were taking place every year, to speak of Athens only. After the pandemic this will change.

Which one of these playwriting trends do you think you do belong to?

I have written plays that are very different from each other. To be honest, I really don’t give much thought to trends; I just write plays that mean something to me.

Apart from your poems and novels, you have written more than 25 plays, including your monodramas. Which of these plays have been produced in a more proper way, do you think? Did you direct them or other directors?

There is no proper way when it comes to the production; there is always a delight when you see a play of yours –made with a limited budget or not– to be interpreted by the directors, the actors, and the rest of the creative crew, even yourself. Of course the result is always pending.

|

| I WANT A COUNTRY / Athens Festival, Greece, 2015. Directed by Marianna Calbari. |

One of the most provocative full-length plays you have written and has been produced in the Royal Court Theatre is “I Want A Country”. Aesthetically, how was the British production in comparison to the Greek production in Athens Festival?

One of the main differences was the number of actresses and actors used. Three in Royal Court, and more than forty in Athens Festival. Both productions were elegant and efficient.

“I Want A Country” could definitely be categorized as a political play which speaks about today’s Greece situation?

When I was working “I Want a Country” the summer of 2012, I was expressing a powerful need to write about what the title of the play suggests. It definitely speaks about the “Greek crisis” but also addressees other societies as well with similar social issues; issues that motivate people to act somehow, since they create fears and frustration to our souls globally. That’s why I think the play had such a good response, not only in Greece.

Where else has it been produced?

Let’s see. In London, in Oxford, in New York, in Rhode Island, in New Delhi, in Mexico, in Brussels, in Lima, Peru, in Zurich...

Is there any upcoming production of the play?

If covid-19 Delta allows, this September in Philadelphia, US.

|

| RIHLA (Indian version of I WANT A COUNTRY), Aagaaz Theatre Trust, New Delhi, India, 2019. Directed by Neel Chaudhuri. |

“Exercises For Strong Knees” is another play you wrote and directed as I remember in the Art Theatre Karolos Koun. You refer dramatically to the crisis of maintaining positions in a company which might be considered as a symbol of society. What did make you to speak about neo-Nazi ideological behaviors and a sort of social discrimination which can end up with serious social challenges in order to survive?

The only answer is: the sad reality of that period. That had motivated this play. During the production in 2013 many people from the audience came to us to tell us similar obscure experiences from their working environment and everyday life.

Another play you wrote and was directed by Christina Christofy in Epi Kolono Theatre is “Lassie”. Why did you choose such a title for your play? Is it, in any way, related to the dog which was the main character of those series made between 1943 and 1941?

Indeed. “Lassie” somehow comes from a place in our childhood. A symbol of the time of our innocence in today’s cynical world.

In “Lassie” we saw a dramatic and rather aggressive challenge between a victim and a victimizer. Based on what social or political context did you create such a work?

The mentality of this play was mostly inspired by how the United Europe pressed Greece to sign the first memorandum in 2010. However, other issues also come to the surface and lead the plot to its formation.

One of your recent plays is “The Things You Take With you” which has been produced under the framework of the festival “on the move” in Royal Court Theatre. What is the gist of your play from your point of view?

It’s all about bittersweet voices of people obliged to leave their countries to find a better place in the western world and who experience its scariest face. This play has a close eye on refugees who take the risk of travelling in order to reside in richer and safer countries to have a better life.

|

| THE THINGS YOU TAKE WITH YOU / Royal Court Theatre, London, UK, 2016. Directed by Richard Twyman. |

What were the main characteristics of the production of “The Things…” in Royal Court Theatre?

It was a very bold and honest direction by Richard Twyman. The British actresses and actors were amazing.

Are you going to perform it in Greece as well?

I hope so.

As a Greek artist, what do you think about the future of theatre in relation to the international trends?

When the pandemic ends, the theatre in Greece and all around the world will be different, I suppose. Only brilliant plays and productions can bring the audience back.

How has the ongoing pandemic affected you and your colleagues since its outbreak?

It is a tough challenge. I believe this situation has affected me deeply, but who has remained unaffected anyway?

What are the problems that Greek playwriting is struggling with nowadays?

Greek is a very small language spoken only by almost fourteen million people globally. Beyond the classics, there is no strong new playwriting tradition in Greece. There is limited playwriting practice at any level of our educational system. Not to mention how the recession affects art everywhere.

May I ask you to share with us an experience you had dealing with a difficult situation with regard to the performance of your work and how you handled it?

In recent years I haven’t really had any sort of difficult situations of that kind. Pretty much, I did enjoy all of my performances. Each one focused on different aspects of every play and I liked that.

|

| THE STATUES ARE WAITING / 1st Ancient Theatre of Larissa, Greece, 2020. Directed by Kyriaki Spanou. Click to watch |

Two productions of yours are on tour this summer: “Statues are waiting” and “One country two centuries later”. What are these plays about?

|

ONE COUNTRY TWO CENTURIES AFTER / Theater of Dodona, Greece, 2021. Directed by Roubini Moschohoriti. |

What alterations has Greek theatre had to make in order to ease the way for the younger generations of Greek or even non-Greek theatre artists?

To be open-minded and open-hearted.

Comments

Post a Comment